Back to News

Cool Jobs

Back to News

Cool Jobs

What does it take to succeed as a female commercial and film director?

This story was updated on 1/11/24.

In 2018, film and commercial director Haley Geffen (SM ‘99) received an email from a mom.

The woman’s 9-year-old daughter had been watching the Sunday Night Football (SNF) Open, which Geffen had redesigned five years earlier to widespread acclaim, earning her her fifth Emmy Award.

In the 2018 version, at the very end of the segment, Carrie Underwood struts through a stadium tunnel, while dancers in bralettes and short shorts twirl and jump around her.

As the scene played out on the woman’s television screen, the woman’s daughter turned to her mother.

She wondered if she was expected to wear clothes like that when she grew older. The idea made her uncomfortable.

The woman encouraged her daughter to write a letter to the producers of the SNF Open, expressing her opinion. The note ended up in Geffen’s inbox with a postscript from the woman, asking Geffen to please hear her daughter’s voice.

Geffen hadn’t worked on the open that year, but she reached out to the people who had. They responded amiably, appreciative of the feedback from a girl and two women who weren’t afraid to speak up.

“In that moment, I was like, ‘Wow!’” Geffen says. “‘I can actually have some influence.’”

In reality, Geffen had already made an impact in the directorial world. She’d been successful by any metric: the prestige of the companies and brands she’d shot commercials for (ESPN, TNT, Warner Bros., Nike, Under Armour, Frito-Lay, Dove), the clout of the celebrities she’d cast (Underwood, LeBron James, Tom Brady), the number of awards she’d won (six Emmys).

All along, working her way through the U-M sport management program, up TV production ranks, and over into commercial and film direction as a 5-foot woman has required a specific strain of daring, persistence, and leadership that few can match.

“I am a strong female,” Geffen says, “but I had to do what I had to do to find my place in that world.”

***

When Geffen was a teenager in West Bloomfield, Michigan, college hopefuls typically chose one of two universities: Michigan or Michigan State. Growing up in a sports-obsessed family who had immersed her in go-blue culture from a young age, she was thrilled when a thick envelope with a U-M logo arrived in the mail.

“If you could get into Michigan, you went to Michigan,” Geffen says. “That was always my goal.”

Geffen had initially thought she might become an athletic trainer; when she’d hurt her ankle playing soccer in high school, she’d been fascinated by how much her trainers seemed to understand about the body and how they could apply it to sports. U-M Kinesiology’s athletic training program didn’t exist at the time, so she chose movement science as a major.

It became clear early on, though, that sport management was the better choice for her long-term. She was much more engaged in her SM electives, like advertising and marketing, than her anatomy and physiology classes. (Failing her final physiology exam sophomore year on account of a bad trip the night before didn’t improve her feelings about the discipline.)

And despite her status as a long-time sports fan, Geffen found she had a preternatural ability to leave that side of herself at home and take on leadership roles when partnering with the big-time athletes who were often in her classes. She worked on projects with Tai Streets and Aaron Shea, both of whom went on to play in the NFL. Heisman Trophy winner Charles Woodson remains a friend from those years.

“I didn’t look at them based on what they did on the field,” Geffen says. “When we were in class together, we were friends and equals. There was a comfort level I had crossing cultures.”

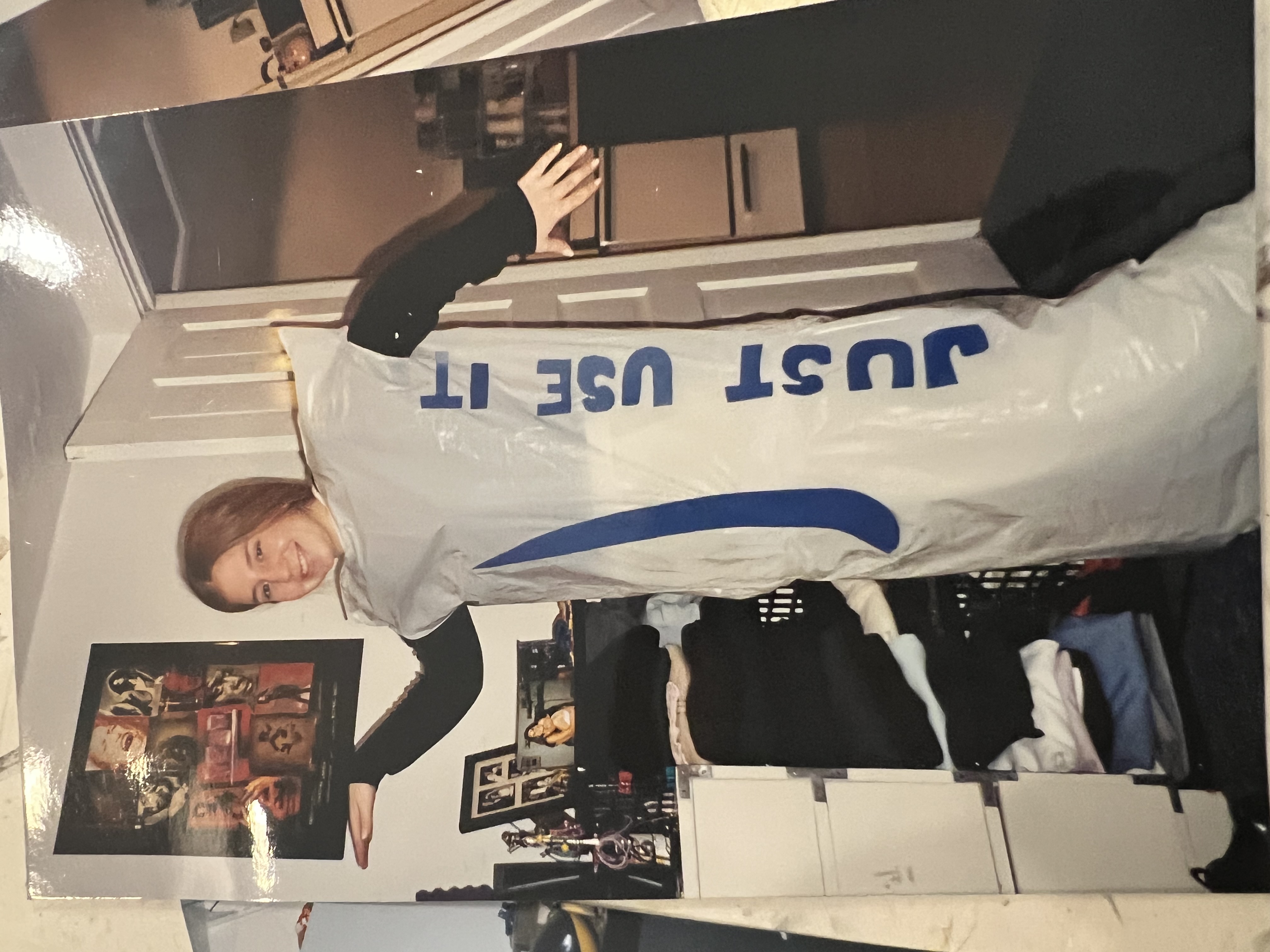

She recalls the time that sport management associate professor David Moore (now an emeritus) assigned her advertising class to develop a brand campaign. Geffen came up with the idea for a Nike condom, with the tagline, of course, as “Just use it.” She wore a garbage bag with a swoosh on it, and the football players in her group presented her in front of the class.

“We were super serious about it, but we also wanted to make people laugh,” Geffen says. “We wanted them to remember that moment.”

“This felt like a pivotal period in my life,” Geffen continues. “I was thinking, ‘Wow, I keep coming up with these fearless ideas. And I’m also leading other people. I’m leading athletes and people that other people are intimidated by.’ At the time, I didn’t have any idea how these skills would translate in my career. Now I know that they were the root of my success as a woman in sports.”

***

Geffen’s career truly kicked off when a friend of hers posed an innocent question during the fall of her senior year: “Do you want to work at the football game on Saturday?”

It was November 1998. U-M was coming off a championship-winning football season, but the team was facing a one-loss Penn State team that was expected to give them trouble. The network needed a bunch of production assistants for this high-profile game, and they were turning to U-M students for help.

Geffen had a sprained ankle, but she didn’t care. For three hours, she ran up and down the Penn State sideline, rolling cable for a handheld camera. She still remembers the score: A 27-0 win for U-M.

After the game, her friends couldn’t wait to go home. Geffen couldn’t wait to do it all again.

For the rest of Geffen’s senior year, she worked on and off for ABC Sports, serving as a production assistant for the Pro Bowl in Hawaii, the Indy 500, and the College Bowl Series (the precursor to the Bowl Championship Series). At the end of the last week of school, she got a call from one of the main ESPN producers, asking if she wanted to be his personal production assistant for the X Games in San Francisco.

Geffen had to pay for her transportation and often for her hotel rooms during these shoots, which her contract salary just barely covered.

“I don’t think I walked away with a penny after that,” Geffen says. “But look what it did for my career.”

What it did was land her a job at ESPN just a few months after graduation.

***

By 26, Geffen was already a producer at ESPN. She moved to New York City to start the show “‘Cold Pizza,” now known as “First Take.” Fifteen people reported to her, including folks who were 15 years older.

“They weren’t thrilled about it,” Geffen says. “But my boss, Mike McQuade, was unwavering in his support for me.”

As she learned how to manage people, branded content was emerging as an industry — and ESPN wanted to be one of the first networks to capitalize on this new monetization opportunity.

“I was a feature producer, and I was all about creative integrity,” Geffen says. “When they told me I had to plug a product in this creative piece I was doing, I lost my mind ‘cuz that didn’t work in my world. Then we got very used to it because that meant I could have bigger budgets for the things I was shooting.”

This led to a job directing in-house commercials and special broadcasts for TNT, which had shared rights to NBA coverage at the time.

“That was my first time crossing over from TV producing into directing commercials that are more similar to episodic television and films,” Geffen says. “It’s different cameras, different equipment. You’re casting actors. It is no longer journalism.”

There were big-time brands involved. Geffen directed a commercial for Gatorade. Then Nike. Then Verizon. Then Volkswagen.

She learned more about advertising, a callback to her sport management studies.

“You never know what the relevance is going to be,” she says about what you learn in school.

At one point, she even shot a music video on a rooftop with the country band Big & Rich for Turner, the parent company of TNT, as a campaign for the Atlanta Braves.

There was a big budget and a huge crew, 80 people or so. After the first take, everyone — the band, the producers, the crew — turned to look at Geffen. For a second, she was confused. Then it dawned on her that they wanted her to tell them how it went.

“That was great,” she told them.

‘Oh my God,’ she said in her head. ‘This is being a director.’

***

Geffen had amassed enough experience to run the show, but she didn’t have the title to show for it. So, eventually, she found a job as an executive creative director and roster director at a production company called Bodega. Using her sports connections, she built up her client base, often working with the same major brands with which she had strong relationships.

But it was a new client that took her to the next level of celebrity: "Sunday Night Football."

In 2012, Geffen was brought on to work on the opening segment with Faith Hill. It was a small shoot with a green screen, and NBC Sports thought more could be done to elevate the concept.

So, the next year, when the network tapped Carrie Underwood to replace Hill, Geffen and NBC Sports vice president of creative Tripp Dixon took the opportunity to dive deeper into film and visual effects. They developed a grandiose shoot, with Underwood seemingly performing in a football stadium, and partnered with well-known artists and lighting directors to create an atmosphere of scale and prestige.

“We turned the set into an event,” Geffen says. “We wanted the NFL players to come to the set and experience what it was like to be a part of Sunday Night Football.”

The effort paid off: Geffen won an Emmy for the production. Alongside her NBC partners, she’d create the next several versions of the SNF Open, reimagining it each year to bring even more spectacle to the shoot.

It was a fulfilling time in her career but also demanding. Both she and Underwood were having children, and they alternated years being pregnant multiple times. And there was a lot of pressure to execute the vision at the highest level given the popularity of the show.

“There was a constant reminder that you’re working on the no. 1 show on television,” Geffen says.

***

By fall 2018, Geffen was tired of being pegged as just a sports director and launched an independent company, Co_ed Studios, with two partners.

She still works with sports clients and recently partnered with the Los Angeles Lakers on a shoot. But she’s also co-written comedy campaigns for GEICO. She directed a three-part film series with Pfizer that paired artists with people who have had cancer to tell their stories through paintings or murals or spoken word performance. She’s made a few of her own films. Recently, she even moved her family to Los Angeles to try to break into directing episodes of TV shows.

And ever since she received that message about the Sunday Night Football Open from the woman and her daughter, she’s changed the way she casts actors and communicates wardrobe to better represent and support women and marginalized voices.

“That’s the best part of owning my own company,” she says. “Supporting women and underrepresented voices in the industry. I don’t look at the early stages of my career as unhelpful. I definitely learned a lot. But there were no real regulations for women. No one gave a shit. So I’m trying to help that change.”

She says she still experiences resistance and discrimination, like when she spends 40 hours writing treatments (a director’s creative vision and plan for a commercial) for agencies that say they want a female director but, in reality, never intended to hire a woman.

“I get the same piece of feedback every time: ‘You really surprised us,’” she says. “‘We didn’t really think you’d be going head to head with this other person.’ So that’s a real mindfu*k. You want there to be this progress. But the progress is not there yet.”

And yet, when Geffen worked recently with LeBron James, the people who’d hired her noticed what helps her to succeed despite the barriers.

After the shoot, one said, “You’re unflappable."

“Yeah,” Geffen responded, “I guess I am.”

Main and last photo by Victoria Stevens