Back to News

Back to News

The case of the missing woman

Something felt, no, looked, different. Sheryl Szady (PE ‘74, MA ‘75, PhD ‘87) hadn’t taken more than a few steps inside the fourth-floor conference room in the Observatory Lodge Building when she spotted it: an unassuming, partially crumbling female bust.

It was January 2018. Nearly three years earlier, Szady had become aware that a bust of Alice Elvira Freeman Palmer — a dominant voice in the burgeoning arena of women’s higher education in the late 1800s — had been gifted to U-M by Palmer’s husband. But no one knew where it had ended up. After spending months investigating, Szady believed Alice to be lost forever, the details of her Ann Arbor arrival having faded with the passage of time.

But here, at a meeting of the U-M Kinesiology Alumni Society’s Board of Governors, Szady thought she may have stumbled across the missing heirloom she had worked so hard to find.

If that were true, how, Szady wondered, had Alice gotten here?

A strong presence, preserved in stone

In 1870, U-M made history when it became one of the first universities in the United States to admit women.

Within the first female cohorts at the university was Alice Elvira Freeman Palmer, who graduated with honors in 1876. She went on to a distinguished academic career that included serving as president of Wellesley College (becoming the first woman to lead an independent, nationally known college in the 19th century) and co-founding the national Association of Collegiate Alumnae, which united college-educated women to increase educational opportunities for women. Freeman Palmer later became a key figure on the Massachusetts Board of Education and the first dean of women at the newly founded University of Chicago.

In recognition of her achievements, U-M awarded her an honorary Doctor of Philosophy degree in 1882, when she was only 27.

After Freeman Palmer died, her husband, George H. Palmer, commissioned several busts and paintings of her to commemorate her contributions at higher education institutions, including U-M.

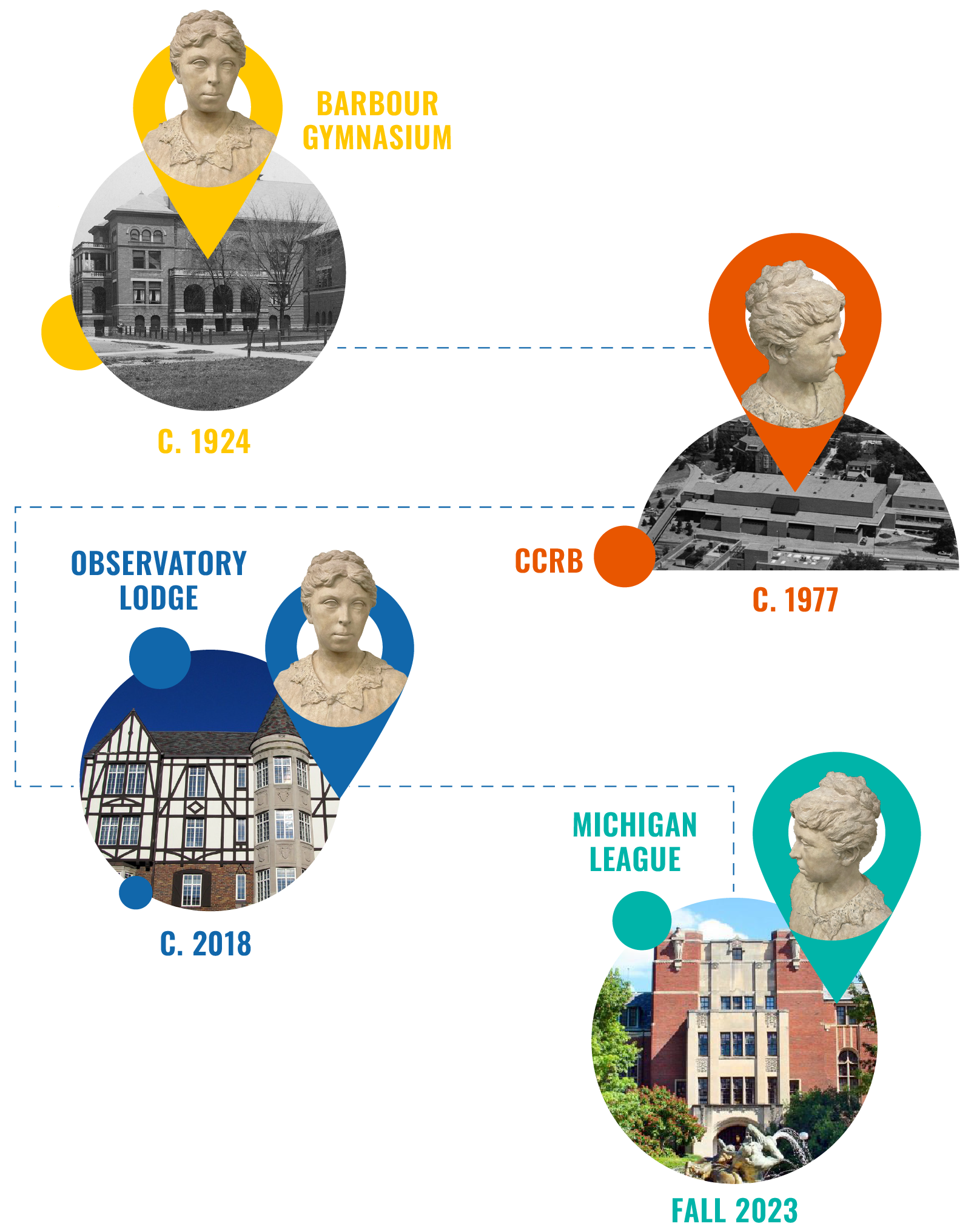

In July 1924, then U-M president M.L. Burton sent a handwritten letter to George, informing him that “the beautiful bust of Mrs. Palmer” was moving from his personal library to its temporary home in the office of the Dean of Women in Barbour Gymnasium, “which is the center of the student life of the women.” From there, Burton assured George that “just as soon as our Michigan League Building is constructed [the student union designated for women at the time] it will be given a place of honor in that building.” Lost, then found

Lost, then found

In February 2015, the contents of Burton’s note caught Szady’s eye while she was researching the Alice Freeman Palmer Professorship Fund. (George Palmer had created the endowment to give a female faculty member “the same privileges and pay as any male member of the faculty.”)

Szady had built her education and career on advancing and chronicling the position of women at U-M. When she’d arrived as an undergraduate student at U-M in 1970, there were no female varsity sports, and she’d led efforts to create six women varsity teams after Title IX was passed in 1972. She later campaigned to award varsity jackets to women during a time when they were only given to men. Over time, she’d become one of the go-to experts on the history of female sports at the university.

Now as a member of the Michigan League Board of Governors, Szady made it her mission to locate the bust of this pioneering woman and bring her back to her intended home at the League.

Szady turned to her wide circle of U-M colleagues and contacts for help. The Michigan League director. Her Friends of the League colleague who handled art acquisition. The U-M Office of the President. The Bentley Historical Library. The U-M Museum of Art. A university committee that oversaw a database of art on campus. The Michigan Union.

No one knew where it might be. Many did not know the bust even existed before Szady’s inquiry. Eventually, Szady exhausted her options and moved on.

“It was lost, broken, who knows,” Szady said. “All I knew was that it had disappeared from the landscape.”

Which made her all the more startled to find an unknown female statue staring at her in Observatory Lodge years later.

With some quick Googling during the KAS Board meeting, Szady determined that the form was indeed Alice.

She asked the Alumni Society staff where it had come from.

“You know, I think Professor [Katarina] Borer is retiring,” one said. “We’re cleaning out her office.”

Connective tissue

It took a bit more sleuthing for Szady to figure out how Alice had ended up in Borer’s cache. She developed a working theory.

Szady knew that Borer had inherited an office in the Central Campus Recreation Building (CCRB), which housed kinesiology students and faculty from 1977 to 2021, from professor emerita Ruth Harris. Before Harris had moved into the CCRB, she’d made her academic home in the back of the Barbour and Waterman gym complex — the same location that U-M President Burton had said would serve as the temporary home of Alice’s bust until the League’s opening.

The more than 35,000-square-foot Barbour Gymnasium’s first-floor rooms originally served as parlors and offices for the Dean of Women and the Department of Physical Education for Women and as a social space for U-M women students. There, Alice’s bust, unknown to passersby, likely watched over fellow women fighting for equality in higher education for decades.

When the Dean of Women offices left the gymnasium complex in 1948, leaving the gym entirely to women’s physical education, Szady surmised that important papers and other lightweight items made the move, but heavier items like the Freeman Palmer bust were likely left behind.

“My guess is Harris took hold of it so it would not be lost,” Szady says.

In 1977, the gyms were demolished to provide room for an expansion to the adjacent Chemistry Building. U-M’s physical education faculty, including Harris, resettled in the newly built CCRB.

Professor Borer moved into Harris’ CCRB office once Harris retired and likely inherited the Freeman Palmer bust.

Though the bust fell into Borer’s possession, it was university property. When it came time for Borer to pack up her belongings, Alice was left behind. No one is quite sure how she found her way to that fourth-floor Observatory Lodge conference room.

But the best whodunits always leave at least one question unanswered.

A celebratory reunion

Szady was able to secure support from the Michigan League to transfer ownership of Alice from Kinesiology. And on a sunny November afternoon in 2023, a group gathered on the third floor of the League to celebrate the fact that Alice had finally arrived at her intended destination.

Szady stood at the front of the room, sharing a condensed tale of her detective work.

“It’s an honor to be here to recognize Alice Freeman Palmer, our patron saint of higher education,” Szady told the crowd of about 40 people.

“Yes!” echoed around the room.

“I’m very happy to be part of recognizing the wonderful aspect that U-M is home to great leaders for women’s higher education,” Szady continued. “It is great to see U-M history come alive.”

You can visit the Alice Freeman Palmer bust on the 3rd floor of the Michigan League. But if you remember seeing it elsewhere in the past, let the author know at [email protected].